- Home

- Herschensohn, Bruce;

Raising the Baton Page 2

Raising the Baton Read online

Page 2

In response Nancy Benford brushed her pig-tailed braids behind her so they went backwards onto his desk.

Mrs. Zambroski was beaming. “Thank you, Nancy. And I’m sure you will be a great teacher.”

Christopher Straw whispered an embellishment to his earlier statement. “A very, very big kiss-up! Like the biggest kiss-up in the whole wide world!”

As other students gave their names and ambitions, Christopher Straw noticed that on the upper right of each desk in this classroom was an inkwell, each one mounted in a hole in the desk, and each inkwell had a shiny near-round metal lid with one flat hinged edge. Each student would be able to open the hinged metal lid to dip the student’s pen in the well’s ink, and then quickly close the lid so the ink still in the well wouldn’t dry.

This presented an opportunity to Christopher Straw: there was the inkwell and there were the pig-tailed braids of Nancy Benford. The pig-tail on the right side of her head was in close range to the ink-well. He opened his inkwell and he very carefully took the end of Nancy Benford’s right side pig-tailed braid and the rest of his activity was easy. It was fun. Her pig-tail went in quite far as he stuffed it in further and further little by little.

She didn’t know it for a long while but, of course, when the school-bell rang for recess to begin she got up, and as she reached to swish her braids from behind her to be in front of her, the realization came on her right hand. The palm of her hand was covered with a gooey black mess. This automatically set her off as she screamed and cried right in front of everyone as they were leaving class and now the ink from her pig-tail was getting on the front of her frilly white blouse that had those annoying little blue sewn replicas of flying birds on it. She made so much noise that Mrs. Zambroski stormed through the rows of desks straight to the scene of the crime where both victim and likely suspect had yet to leave.

“What’s going on here!?” she demanded to know as she looked back and forth from Nancy Benford to Christopher Straw. “What’s going on here!? Huh? Huh? Huh? Huh?”

“Looooooook!!” Nancy said. “Looooooook, Mrs. Zambroski!” She motioned her head toward the evidence.

Christopher Straw whispered, “Tattle-tale.”

Mrs. Zambroski glared at him. “Did you do that? Answer me, young man, did you do that?”

“No, Mrs. Zambroski,” he lied. “Her hair-things are real long and one just must have fallen in the inkwell. It can do that real good.” And then he corrected himself. “It can do that real good, Mrs. Zambroski.” He thought that adding her name at this moment was a sign of respect, certain to influence her generosity of attitude.

“Are you lying to me?”

“No, Mrs. Zambroski. It just must have fallen in the inkwell. My inkwell is sort of broke because it’s hard to close.”

Mrs. Zambroski inspected his inkwell by quickly opening and closing it a number of times. Unfortunately, his lie was not well prepared. The inkwell was not at all hard to close.

After Mrs. Zambroski regained her composure well enough to be a real teacher, she told him the story of George Washington chopping down his father’s cherry tree and then admitting his misdeed to his father, saying “Father, I cannot tell a lie.”

She told him about this right in front of Nancy Benford who had a look of victory on her face. Even her freckles were looking victorious.

“Now,” Mrs. Zambroski asked Christopher Straw, “Are you George Washington or are you a coward?”

“Neither, Mrs. Zambroski.”

“What do you mean, ‘neither,’ young man?”

He thought fast. “I don’t know.” Good thinking.

“You don’t know?”

“I’m not sure, and I want to tell the truth, so I can’t say either one.” Very good thinking.

She didn’t know what he was talking about and neither did he. “Think,” she said. “Don’t rush to answer. Patience is a virtue.” What a quick mind to drag that one up. “Think. Then answer me. Truth, you should know, is stranger than fiction.” She had so many great pieces of wisdom packed into her mind.

He hesitated and then said, “I’m more like George Washington.”

“Christopher Straw! Christopher Straw! I’ll remember that name, young man! And you—” she pointed to Nancy Benford, “Let’s you and me go to the Girl’s Room and I will wash that mess of ink out of your hair!—you poor thing!”

Through her weeping noises Nancy Benford managed to say, “Thank you, Mrs. Zambroski!”

Finally Christopher Straw was allowed to leave for recess and he was so glad to get out of there without going to prison that he ran out passing the now-open classroom door, down the hall, downstairs and out the school-door to the playground along with the other kids who were screaming in delight and he was yelling the melodious statement, “Schools Out! School’s Out! Teacher Let the Monkey’s Out!” Then he felt embarrassed because Nancy Benford holding Mrs. Zambroski’s hand was out there and they probably saw and heard him and he saw Nancy Benford shake her head in absolute disgust.

As the semester went on and eventually came to its end, and then when more semesters came and went from current to past, what bothered him most about Nancy Benford was that she was beginning to look pretty, and then prettier and prettier. She stopped wearing those pig-tailed braids. Instead she wore her long blazing red hair down to her shoulders and beyond.

And she didn’t say he made her sick anymore; she just ignored him which was worse to him than hearing her say that he made her sick. That’s when he learned it would be better for a pretty girl to hate him without reason rather than offering him indifference. When she said he made her sick at least he was important to her. This new indifference meant he was not even in her thoughts at all.

He began to like Nancy Benford in a strange kind of way.

A lot.

Pretty girl. Really pretty.

Life takes incredible turns.

But no matter how intoxicating she became, he couldn’t help but wish he had put both of her pig-tails in the ink.

THEME TWO

THEN THERE WAS MISS OSBORN

LIKE MOST OF THOSE HIS AGE, Christopher Straw ran with his arms flailing beside him while older people were satisfied walking at a reasonable pace; even a stroll and some even slower than a stroll and with little arm movement. But Christopher Straw was much too new to the world for all of that slow stuff. He would soon be in such a hurry that it could appear that a band of armed assailants were chasing him. But since no one was chasing him, Christopher Straw’s youth was often a goldmine of adventure. Unlike new things that hurt, like that terrible day when Nancy Benford had told him she hated him, he ran for the same reason that most of his age ran; to see all those things that could be seen while the sun was up—and that was because everything was so brand new. The regular taller humans had probably seen those things hundreds of times, maybe thousands of times, but Christopher Straw could see new things with almost every glance, and beyond that he could also smell new things and hear new things and taste new things and touch new things with little if any difficulty.

There was the thrill of walking in a small vacant lot which was perceived at the time to be a giant field or maybe it even looked like a forest that could be explored like a pioneer, and above it a deep blue sky with the emerging heaviness of gray on the horizon and the scent of a coming rain and the thrill of seeing birds who knew for sure that the rain was coming and so they would fly in magnificent formations and there was the chirping of a foreign-sounding melody being sung to other birds to tell them about something probably other than weather.

And there were the inventions of Man that seemed to have passed by the attention of taller generations. There was the taste of the small candy confections that were called Sen-Sen; tiny black licorice squares that came to the extended hand through a hole in a match-box-sized red cardboard box. Those miniature boxes were easy to hide because of their Lilliputian size. The Sen-Sen’s from within them were intriguingly spicy-hot which appeared

to be made for older people but he, somehow, had been granted a preview of what he would be able to taste in years to come.

And there was learning about competition because without such a small box and without the name of Sen-Sen’s, here were small round and red cinnamon candies that were not real Sen-Sen’s but gave a somewhat similar taste—not really the same and not as easy to hide but were eatable.

And there was the feel of the back of a frog that was hoped would become a friend, but no luck because it would quickly jump away out of fear of Christopher Straw’s exploring hand. Frogs did not have the same appreciation of newness as did small human beings.

When winter came there was the excitement of snowflakes falling all over the ground and making a thin white blanket on every parallel horizontal tree-branch and there was the ability to make and throw snowballs. How could anyone be content with staying inside with outside having such a variety of sight and feel?

Seasons known before then came back, one after the other just like last year. There was an unexpected rhythm to most of this. Disinterest in repetition was not yet an issue in life because at that age there was so little of it. The few repeats encountered were welcome to Christopher Straw because he was proud that he had now lived long enough to be aware of reappearance.

One of the particularly pleasant additions to his life came two years later when he entered the grade of 4-B. It was his teacher, Miss Osborn, in 4-B’s September and she was, to him, newer than anything else so far this semester. She touched something inside of him similar to, but even better than how he felt when he first noticed that Nancy Benford was getting pretty. How many more incidents would be there to bring about more of that feeling inside of him? Does each incident get better than the preceding one? When do you just blow up, and is that the end of you?

He stared at his new teacher throughout September and October and by November he was ready to ask her to marry him. Significantly that was when the leaves of Pennsylvania were golden while others were red, and some of the branches of trees were already barren with mounds of fallen leaves on the sidewalks and yards. Christopher Straw was now nine years old and his Miss Osborn was not anything at all like Mrs. Zambroski. Miss Osborn, he assumed, was some one-hundred-fifty years younger than Mrs. Zambroski (give or take one or two years) and looked something like the movie star, Betty Grable, who he had seen in a movie called “Million Dollar Legs.”

Like all teachers, Miss Osborn had no first name. That never bothered Christopher Straw before but now it bothered him a lot. What if she asks him to call her by a first name? Maybe she would make up the name, Beautiful Betty. Then what?

In this new semester and new classroom Nancy Benford did not make the mistake she had made only once before when she had sat in front of Christopher Straw. This time she sat one row to the right of him where her pig-tails were safe. Not that he cared anymore. His interest was neither anger nor lust of Nancy Benford, but instead he was fastened on the dazzling good looks of Miss Osborn.

Beyond her extraordinary prettiness, what added to the delight of having her as his teacher was that she talked with enthusiasm about astronomy and told the class that the next complete solar eclipse would occur in about a year and a half on February the 4th of 1943 and she hoped to go to Japan to witness it because the view there should be excellent. When he rose from his seat and said he would like to go there with her, she laughed and then said she would like to have the entire class go there with her. (As it worked out, of course, neither Miss Osborn nor anyone in her class would make the trip to Japan in 1943 unless one of them would be part of a bombing mission.)

“Christopher, you’ll have plenty of opportunities to see solar eclipses in the future! There will be one you can see in Canada in 1945, and since you’ll still be in school in 1945, you should probably wait even longer; because even better, you can see one from right here in McConnellsburg in 1954.”

“1954!?” he asked with disappointment. Wasn’t that number too far ahead to even think about it ever being a real year?

Miss Osborn sensed his depression. “Is that too long for you to wait?” she asked.

“That’s forever! How old will I be then?”

“You tell me. How old are you now, Christopher? Eight or nine?”

“Nine! Not eight! Eight was a long time ago! I’m nine!” And then louder he said, “I’m nine!” Of course he repeated it with volume because he wanted her to be sure to know that he had left behind any remnant of his childhood. He was probably close enough in age now for the two of them to get married. “How old are you?”

For a while she was speechless, and then she smiled widely and said, “Christopher, you and every other boy in the room should know that you never ask a lady her age. But that doesn’t mean a lady can’t ask a boy or a young man his age! Now, you figure out how many years will pass until the year is 1954?”

“Thirteen years!” Miss Know it All, Nancy Benford, the giant of all information and calculations and smartness and authority and pomposity said quickly.

“Very good, Nancy! Now, Christopher, from you: how old will you be in 1954? I don’t know the date when the eclipse will be in 1954 but let’s assume it will be exactly thirteen years from today. How old will you be then?”

He started counting on his fingers by spreading out his hands on his desk, whispering each number as he progressed from his right to his left hand, but not fast enough to shut up Nancy, who said in a soft voice but loud enough to be heard, “Twenty-two.”

“Shhh!” Miss Osborn said. “No, Nancy. I want Christopher to do it.”

He continued to look down at his spread-out hands and nodded. “I was just going to say ‘twenty-two,’ Miss Osborn. Twenty-two. It’s twenty-two.”

Miss Osborn nodded. “See?” she asked without looking at anyone in particular. “He could do that without anyone’s help!”

Christopher smiled with a shy expression as he looked away from Miss Osborn, moving his hands from in front of him and he stared at his vacant wooden desk.

Then Miss Osborn asked, “Christopher? You did do that without any help, didn’t you?”

He nodded but he didn’t say anything.

“Is that right?” She wanted affirmation said by voice.

He nodded again.

“Then that’s very good.”

But it wasn’t very good. Even he knew that.

“Now,” Miss Osborn said, “for just a moment let’s go on to look at the sky as though we had a giant telescope like the ones they have at observatories. And pretend that we can see every planet in our solar system. And do you know what it would look like if we could—”

“Miss Osborn?” Christopher interrupted.

“Yes, Christopher?”

He hesitated and then said, “Nothing.”

She looked at him with her head tilted, a characteristic that came from her inborn femininity, and she gave a mystified look along with her tilted head. “What?”

“Nothing.”

Now she tilted her head to the other side. “Oh, I think there was something. Wasn’t there something, Christopher?”

This time his hesitation was very long and Miss Osborn let it go on as long as he wanted.

But when the silence got to the point that it was overbearing to him, he said, “Yes, Miss Osborn. There was—something.” He hesitated again but not for long this time. “I lost count on how old I would be in 1954, but I heard Nancy say it. That’s how I knew I would be twenty-two.”

That surprised Miss Osborn and, even more, it surprised Nancy Benford, and most of all it surprised Christopher himself who had learned much more about honesty from Mrs. Zambroski in semesters back in time than he ever thought he had learned.

“You have a marvelous sense of values, Christopher,” Miss Osborn said. “That means far more than any test you need to pass in this class.”

Nancy Benford was looking at him not with indifference which was good enough—but with admiration, and even flirtation. Her look wa

s so flirtatious that she quickly brushed aside long locks of her red wavy hair from in front of her right eye just like the movie star, Veronica Lake, so he would be sure to see her blink a couple times.

And he just looked away from her without any expression at all on his face.

He was the indifferent Christopher Straw.

He was getting smart on all fronts.

Not bad for progress in growing up early.

THEME THREE

THE HOLIDAY

HONESTY, for which he was so richly complimented in public praise, made a great change in him. Because of the words of Miss Osborn and the quick blinking flirtation of Nancy Benford, for Christopher Straw the consistency of honor became an ambition. That was not to minimize but to maximize the earlier things in which he wanted to excel. After all, he thought, George Washington’s reputation of honesty was not the only virtue of his life or he wouldn’t have stood up in a rowboat rocked by heavy waves in the Potomac River and then he became Father of his Country. Those things didn’t happen because of honesty as much as other qualities of his character. And so Christopher Straw reached further into those things in which he wanted to excel.

“Learn everything you can,” his father told him. “Know things. Many things. But keep in mind that a lot of people know many things. As good as that is, know one thing—one thing better than anyone else knows it. Better than anyone else in the world.”

“What should it be?”

“Your choice. If you don’t know yet what it is, then let your passion lead you to it.”

“Going to the moon?”

Without any hesitation his father nodded and said, “Do it. Follow it. Daydream about it. Dreams make things happen. And don’t be afraid even if you make mistakes on your way—to the moon. You can avoid most mistakes if you find those who failed at things in their days that you do successfully in your dreams. Find out why they failed and then you don’t duplicate their failures. Can’t beat it. And—oh, yes—be good. Be good in all things—in big things—in little things. No, no. I take it back. There are no little things. If you think you have been good in nothing more than a little thing—then you are the little thing.”

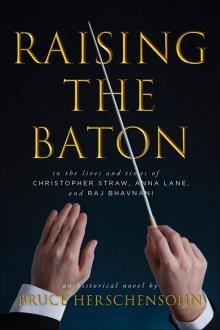

Raising the Baton

Raising the Baton